Why I Love ... Scottish junkies

The film that defined a generation of vibrant British cinema was an invigorating, challenging blast of fresh air, and tells us something about Christian mission.

I was the perfect age for it, the very definition of the target market - even if I don’t like to think of myself as a market. It was the year after I’d finished university, and I was taking a year out - but instead of going round the world to find myself, I did a thing that only Christians seem to do and raised an amount of money, effectively paying for the privilege of working as an intern for a Christian organisation for a year. It was hard work, but it was fun. That aspect of my life stage wasn’t the target market, but much else was - making my world, still working out who I was … and from Edinburgh.

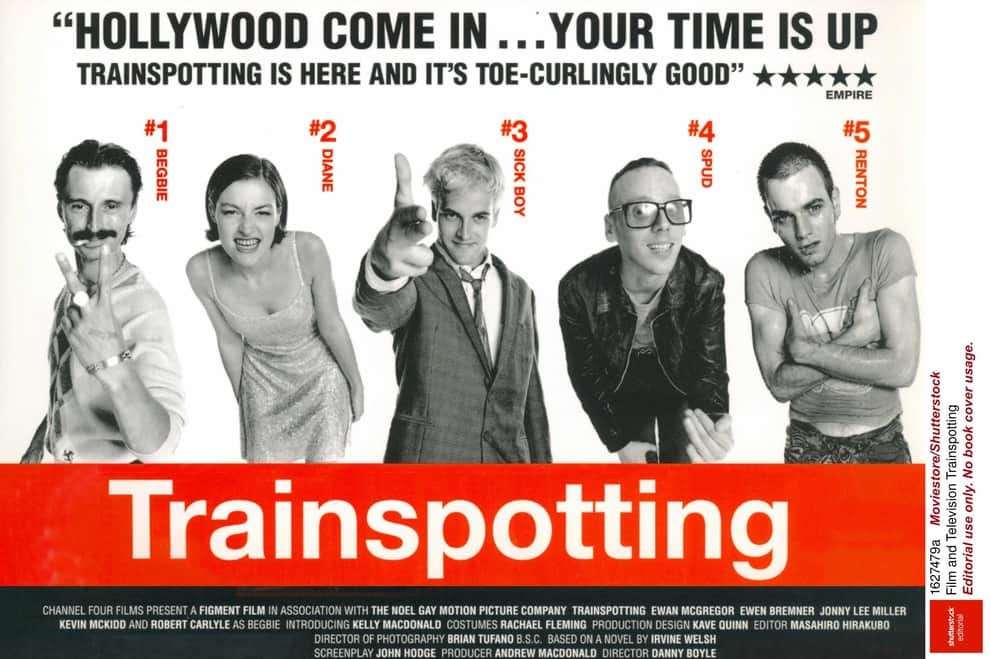

The film in question - 1996’s Trainspotting, directed by then-young British director Danny Boyle - was generating vast amounts of pre-release hype. The director’s first film - the darkly funny noir-ish Edinburgh set thriller Shallow Grave - had proved a low-key hit. This second film was an adaptation of Irvine Welsh’s cult novel of the same name, often thought to be unfilmable; a dark, difficult, explicit book about Edinburgh drug addicts, written in broad Scots. But the combination of exciting young acting talent, a buzzy director, and an iconic marketing campaign sent expectations sky-high.

It turned out to be the sort of lightning in a bottle that was impossible to replicate. It launched the careers of several now-globally lauded British acting stars (Ewen McGregor, Johnny Lee Miller, Kelly Macdonald, Robert Carlyle, Peter Mullan … to name just a few) and cemented Boyle and his screenwriters as prodigious talents. Boyle would go on to win Oscars (Best Picture for Slumdog Millionaire) and direct the memorable, vibrant opening ceremony to the London Olympics in 2012. Seeing Trainspotting for the first time was a dazzling, unforgettable experience. It was a packed cinema in the first week of release, in a Scotland desperate to see itself represented realistically and vibrantly on screen. The film was a riot of innovative techniques; the now much-pastiched opening monologue-montage set to Iggy Pop, innovative editing, explicit scenes of sex, drug-taking and its effects, and a soundtrack to define a generation. People were offended - of course, they were; there’s always some interest group ready to grasp the publicity of offence, even in the pre-internet days. I was so knocked out, blown away, disorientated by the heady experience of the film in a packed Scottish cinema that I didn’t notice that as I was being dropped off by one of the girls I’d seen the film with, I was being asked out by her in the process. I phoned her later to check; she had indeed asked me out. Reader, I said no.

Trainspotting was showing me something fresh about what cinema - British cinema - could be. Not a stuffy costume drama; this was something from a place I knew, about life as it was lived now. Edinburgh had been the AIDS capital of Europe - thanks in large part to the heroin explosion in the city. This was a film about that; something my parents had sheltered me from but you couldn’t help but know was out there - even if Edinburgh has always been disturbingly adept at hiding its underclasses away from polite, moneyed society. Controversy came because the film was fast and funny; some felt it was showing drug addiction itself was fun. Some addicts reported being triggered by its depiction of the addiction experience. This was no ‘Just Say No’ message - we know now that that po-faced, worthy, instruction to abstain is destined for failure if the thing you’re trying to stop people indulging in at least looks fun. If something appears to be fun and transgressive, then you can pretty much guarantee that people - especially young people, desperate to rebel and define themselves - will say ‘yes, actually.’ Back then, ‘Just say no’ is what you were expected to say, and Trainspotting appeared to encourage ‘yes’. In reality, the filmmakers had worked with recovering drug addicts, trying to make something authentic to their experience. Their experience was this uncomfortable reality; that drugs offer an initially fun, exciting escape from mundane, boring, deathly reality. The film is structured like a drug trip - a rush, a cataclysmic punch in the face from reality, a series of partial or wholly failed attempts to remake life in the wake of addiction after the awful has hit home. Nobody can watch Trainspotting and seriously think ‘I’d like to live like that’; but it’s uncomfortable because it presents a society with its culpability in the way it leaves people behind, grasping for attention and relationships and approval - and offers something that suggests these will be given by a white powder. Unlike ‘Just Say No’, this reading of reality doesn’t fit on a t-shirt; but it explains why addiction remains a tempting reality amongst the surface-level success stories of stock traders and business people as well as those cut adrift in an underclass. That Trainspotting’s take on addiction has proved more enduring and relevant all these years later than the simplistic ‘Just Say No’ should make us all think a bit more deeply when we're tempted to preach a gospel of simple refusal to temptation when realities are more complex, and in need of a more nuanced, compassionate response.

Over the years Trainspotting has become something I repeatedly return to, a text which gives me direction and hope, a light of something more hopeful. About dwelling with and listening to suffering people, rather than speaking at them, waiting for them to download my or someone else’s wisdom. That is, after all, how God ultimately gets people’s attention - by taking on flesh and blood, living amongst and listening and working. Yes, of course, He preached too. But He did so after around 30 years of simple living and being. Trainspotting is one of those anchors that challenges me to listen first, to listen to reasons why. Occasionally I manage to do so, The fact that the film remains fast, funny, shocking, disturbing and thrilling is a testament to its remarkable level of craft across the board. That it does so on the streets of the city I grew up in and will always in some way think of as home, was the lever by which it opened the door to my heart; the soundtrack an addictive, brilliant gateway drug. Danny Boyle remains my favourite filmmaker, one in whose films I always find something to enjoy and make my own, and revisit time and again. Many of my most memorable film experiences are courtesy of his direction; Trainspotting was the film that showed me that this was a voice I could hear.

Trainspotting’s Iconic Opening Scene

An article from the British Film Institute about the film’s legacy

Also in this series: